About Our Reenacting of the Siege – 27 February 2012

The students of the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs’ HIST 4160 – A Crossroads of Civilizations: Spain and North Africa, as well as members of the Historical Engineering Society (HES), demonstrated an operational medieval trebuchet (a catapult-style device) to launch watery orbs at a medieval model of the city of Zaragoza, Spain. Commanded by our queen, members of the Spanish aristocracy, and the queen’s engineer, this joint student-faculty project re-enacted the historic siege of Zaragoza of 787 c.e. The siege of Zaragoza is a complicated moment in history in that it invites the unexpected – Christians rode to the rescue of Muslims. We assembled on the West Lawn at approximately 1:40 pm and began our attack on the city by 2:00 pm.

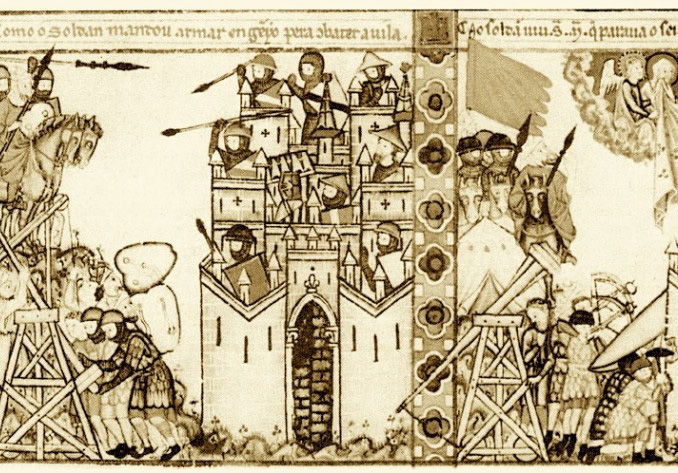

Our five-foot tall trebuchet, built according to historically-accurate standards, is based on one depicted in the 13th century Castilian monophonic songs known as the Cantigas de Santa Maria (Canticles of Holy Mary).

Our trebuchet is constructed with no ingenious devices of modernity – only – sturdy hardwood white oak, glue and adhesives, wooden peg fasteners, and limited pieces of iron. (Okay, we’ve cheated a bit and used a ‘modern’ blacksmith to assist us in the interest of safety.)

In addition to our siege of the city, we presented short displays that described: (a) the history of the siege of Zaragoza, (b) Frankish King Charlemagne and his connection to this siege, and (c) Spanish Castilian King Alfonso X “The Learned” and the Cantigas de Santa Maria, and (d) the history of the trebuchet. (Read more below.)

Best, Dr. Roger L. Martinez, Department of History

Videos from the Event

UCCS Cantigas de Santa Maria Trebuchet – Pre-event test shot (click for video)

Chancellor Pam Shockley-Zalabak – “wills it” – our attack – UCCS Cantigas de Santa Maria Trebuchet

Prof. Christensen orders death to the queen’s enemies – UCCS Cantigas de Santa Maria Trebuchet

Dean Peter Braza wishes a scourge upon them – UCCS Cantigas de Santa Maria Trebuchet

Provost David Moon calls upon all to spite our enemies – UCCS Cantigas de Santa Maria Trebuchet

Prof. Michael Calvisi orders: Down with the castle walls – UCCS Cantigas de Santa Maria Trebuchet

The Siege of Zaragoza (787 and 789 c.e./a.d.)

-By Kelly Johnson, UCCS HIST 4160 student

During the 8th century, the Ebro Valley in Northern Spain was a desirable dominion for numerous conquerers leading to opportunistic alliances and sieges for supremacy. The Arab factions desired control of Northern Spain and the Franks wanted to suppress Arab expansion and prevent Islam from crossing over the Pyrenees mountains into France. The Frankish King Charlemagne desired the dominion south of the Pyrenees for political and religious pursuits.

However, conflict between Arab factions for the control of Zaragoza made alliances difficult for the Franks. In 777 CE., the son and son-in-law of Sulayman ibn Yaqzan al-Arabi were sent to establish an alliance with Charlemagne because of their opposition to the caliph in Cordoba. They arrived in Paderborn, Saxony to address King Charlemagne at an assembly asking for assistance in the struggle for supremacy in Zaragoza.[1] King Charlemagne was “dazzled by illusion that he could tear away from Islam a considerable part of Spain”.[2]

Charlemagne saw this as an opportunity and agreed to an alliance. In 778, Charlemagne sent two armies in opposite directions over the Pyrenees Mountains. One army headed west over the Pyrenees toward Zaragoza, while the other army was en route east for Barcelona.[3] While Charlemagne’s armies made their way towards Zaragoza and Barcelona, Sulayman was murdered by his associate Al-Husayn.

A power struggle between Abd al-Rahman I and Al-Husayn for Zaragoza resulted in a short lived battle resulting in Al-Husayn’s ascension as sole master in Zaragoza. Charlemagne believed that he had allies within Barcelona and Zaragoza; however, as he approached Zaragoza he realized he was unable to enter into the city and that the alliance had been broken.

The troops that headed for Barcelona returned to Charlemagne’s army and after trying to lay siege for a short period, Charlemagne decided to retreat and head west across the Pyrenees back to Gaul. Upon their retreat, Charlemagne’s army was besieged by the Basques at the pass of Roncasvalles, a battle later romanticized, glorified, and falsified in the French poem entitled “Song of Roland” and illustrated in the French manuscript “Grandes Chroniques de France” (Figure 1).

At Pamplona, Abd al-Rahman I had sent an army to rid the city of the Franks. The Franks destroyed by the Basques and besieged in Pamplona could no longer invest in the battle for the Ebro Valley and retreated heading North to Gaul. The agreement between Abd al-Rahman I and Al-Husayn resulted in the exchange of Husayn’s son as a hostage. A year later the agreement was broken and Husayn’s son was killed. The Umayyad empire was spreading North and eventually the Husayn conflict gave them the opportunity to take control of Zaragoza.

In 779 the Umayyad Amir with the aid of 36 mangonels, a prior form of the trebuchet, took Zaragoza by storm and they had finally conquered the Ebro Valley.[4] King Charlemagne’s desire for Frankish superiority within Spain was overshadowed by the Civil Wars between Arab factions for legitimacy.

Bibliography

Collins, Roger. The Arab Conquest of Spain: 710-797. Blackwell Publishers Ltd: Oxford, UK, 1989.

Ganshof, Francois. “Charlemagne.” Speculum, Vol. 24, no. 4 (1949): 520-528. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2854638 (accessed February 10, 2013).

Images

Battle of Roncevaux (778). Grandes Chroniques de France. Illuminated Manuscript from the 14th Century. Repository: Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. http://library.artstor.org/library/iv2.html?parent=true (accessed February 10, 2013).

[1] Roger Collins, The Arab Conquest of Spain: 710-797, (Blackwell Publishers Ltd: Oxford, UK ,1989), 177.

[2] Francois Ganshof. “Charlemagne,” Speculum 24, no. 4 (1949): 521, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2854638 (accessed February 10, 2013).

[3] Roger Collins, The Arab Conquest of Spain: 710-797, 179.

[4] Ibid., 180.

Charlemagne, Zaragoza, and “The Song of Roland”: Fact and Fiction

-By Kelcey Vogel, UCCS HIST 4160 student

Charlemagne was an eighth century emperor in Europe who was known for being the epitome of a Christian king. One of the most famous and lasting references to Charlemagne was “The Song of Roland,” which told the story of Charlemagne’s siege of Zaragoza. Yet, this story is not all historically accurate. Like many poems and epics throughout history, this was utilized for more than just the purpose of documenting history. It was used for Christendom to inspire other Christians with “the showdown between right and wrong” as the notorious Charlemagne battled Muslims in Spain. Charlemagne ruled the Frankish kingdom to the north of Spain during this time, and he had done much to push the Muslims south to the Pyrenees. Charlemagne’s ultimate goal was to force the Muslims farther south than he already had and take up defensive positions along the Iberian side of the mountains. In this way, Charlemagne embraced the opportunity when the governor of Zaragoza, who was a Muslim, asked for Charlemagne’s aid to rebel against the Umayyad emir “a new Muslim ruler in Spain”, Hisham I. The march for Zaragoza began in 778 when Charlemagne led his army through the pass of Roncevalles and into Spain. Once in Spain, he gathered supplies on credit from a Christian community in the north of Spain. Then, he continued on to Zaragoza. Yet, his efforts to get to Zaragoza did not seem to be worth the effort as the siege of Zaragoza failed even with the help of the Muslim rebels. Charlemagne left to return to his kingdom, yet he failed to pay his debt to the Christian community he bought supplies from. As he was traveling back through the pass of Roncevalles, the Christian community he owed a debt to attacked his rear guard. In this battle, the casualties included Charlemagne’s nephew Roland, among many others. From the siege of Zaragoza and the resulting battle with the Christian community Charlemagne owed a debt to, “The Song of Roland” was created by Turoldus. This epic was written in a different time period from when the battle actually occurred, one where the inspiration for fighting against Muslims was needed (i.e. the eleventh and twelfth centuries). Because of this, many of the details of “The Song of Roland” were not historically accurate—they were skewed to make the Christian Charlemagne seem heroic while fighting against the Muslims. For example, Charlemagne did go to Zaragoza in the epic, but his motives were to take it for himself and Christianity. Yet, historically, this is false, as Charlemagne did not want to take the city for himself—only to help another Muslim ruler defeat a rival Muslim ruler. Another way in which “The Song of Roland” is untrue and geared toward a pro-Christian audience, is that it is not the Christian community angry about Charlemagne’s debt to them that attack his rear guard and kill Roland. In “The Song of Roland” it is Muslims attacking Charlemagne as he returns home. Despite many historical inaccuracies, “The Song of Roland” has survived the ages as an inspiration for pro-Christian activities and as an account of the siege of Zaragoza—despite not being entirely correct.

Bibliography

Lowney, Chris. A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. A Concise History of Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

King Alfonso X and the Cantigas de Santa Maria

-By Megan Bell, UCCS HIST 4160 student

King Alfonso X was an influential ruler in the Spanish regions of Castile and Leon between 1252 and 1284. Alfonso was born in Toledo, a city in central Spain, to a politically powerful family in the year 1221. Alfonso learned about military affairs from his father, Ferdinand III, and fought alongside him. Prior to his kingship, Alfonso was highly educated and even assisted in the development of Castilian Spanish, a new literary language of the time. His qualities as a leader are evident in the titles he was given, i.e. King Alfonso “the Learned” or “the Wise.” Additionally, he fashioned himself as the king of three religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – and sponsored several intercultural translation projects in Toledo. His devotion to the advancement of Spain was not limited to academics solely. While Alfonso’s army experienced military defeats late in his kingship, he held off revolts from the Muslims in 1252 and then the nobles in 1254. After these victories, it is not surprising that he accepted the title, Holy Roman emperor, in 1256.

King Alfonso X supported the creation of the Cantigas de Santa Maria or “Canticles of Holy Mary,” a collection of 420 narratives, devotional, and liturgical poems. The Cantigas de Santa Maria are dedicated to the Virgin Mary, an important figure in the Catholic faith, who is honored by the Church to this day. The compositions were written in medieval Galician-Portuguese under Alfonso’s direction from 1252 to 1284. Here is a translated excerpt of Cantiga Number 10:

Rose of roses and flower of flowers,

Lady of ladies, Lord of lords.

Rose of beauty and fine appearance

And flower of happiness and pleasure,

lady of most merciful bearing,

And Lord for relieving all woes and cares

The Oxford Cantigas de Santa Maria Database suggests that the collection “was seen by him [Alfonso X] as an important part of both his political survival and his personal salvation.” The collection of Cantigas offers information about the period, as historian George Greenia claims that “the Cantigas [. . .] provide the best graphic record we have of the life and society of thirteenth-century Europe.”

It is likely that our trebuchet reflects the design of those used in past sieges. The Cantigas de Santa Maria provides historians with insight into King Alfonso X’s religious devotion and governance in Spain during the Middle Ages.

Bibliography

“Alfonso X, El Sabio. Cantigas de Santa Maria: Num. 10.” Washington University. http:// faculty.washington.edu/petersen/alfonso/cant10e.htm.

Bell, Aubrey F. G. “The ‘Cantigas de Santa Maria’ of Alfonso X.” The Modern Language Review 12 (1915): 338-348. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3712624.

Burns S.J., Robert, I. “Chapter One: Stupor Mundi: Alfonso X of Castile, the Learned.”

http://www.cristoraul.com/ENGLISH/readinghall/UniversalHistory/Spain/Alfonso_X_the %20Learned.htm.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Alfonso X.” http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/ topic/14725/Alfonso-X.

Greenia, George D. “The Politics of Piety: Manuscript Illumination and Narration in the Cantigas de Santa Maria.” Hispanic Review 61 (1993): 325-344. http://www.jstor.org/stable/ 475069.

Humphries, Paul Douglas. “‘Of Arms and Men’: Siege and Battle Tactics in the Catalan Grand Chronicles (1208-1387).” Military Affairs 49 (1985): 173-178. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/1987537.

“Introduction to the Cantigas de Santa Maria.” The Oxford Cantigas de Santa Maria Database. http://csm.mml.ox.ac.uk/?p=intro.

Keller, John E. “An Unknown Castilian Lyric Poem: The Alfonsine Translation of Cantiga X of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.” Hispanic Review 43 (1975): 43-47. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/472510.

Rosenwein, Barbara H. A Short History of the Middle Ages. New York: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

History of the Trebuchet

-By Rich Wittenbrook UCCS HIST 4160 student

The trebuchet was the premier siege weapon of the Middle Ages and was specifically designed to hurl massive stones at a fortified position, most often castle walls. Some say that a single trebuchet could launch around 2,000 stones or projectiles in a day. They evolved over time from human powered “traction” devices, to gravity assisted, “counter weight” devices. This device (the counterweight trebuchet) was a product of multiple civilizations and is one of the greatest examples of multiculturalism in in the field of technology.

The date of conception of the first counterweight trebuchet is not exactly known. The earliest visual depiction of a counterweight trebuchet was found in a medieval Islamic manuscript written by Mardi al-Tarsusi. This manuscript depicts a counterweight trebuchet that was illustrated in 1187 c.e. According to John Norris, the first recorded use of the counterweight trebuchet came at Cremona, Italy, in 1199.cIt is believed that Islamic civilizations were designing, building, and employing traction trebuchet as early as the 690s.

The advantages of the trebuchet, when compared to a normal torsion catapult (the weapon of choice during the Roman Era), were staggering. Some trebuchets were built with 50-foot launching arms and used counterweights of 20,000 pounds, which meant the machine could launch a 300-pound stone up to 300 yards with great accuracy. Vernard Foley has said that the “counterweight trebuchet played a role in the greatest single advance in physical science of the medieval period.” Additionally, it was the first fully mechanized pivoting-beam artillery weapon powered exclusively by gravity.

There are three major characteristics about trebuchets that make them unique. The use of a long throw arm on a pivot, the use of a counterweight and the use of a sling. The counterweight trebuchet operated off of momentum provided by the dropping of a massive weight, the traction trebuchet used momentum created when a group of men pulled on a set of ropes at the non-launching arm of the machine. The arm would pivot in the center and launch the projectile through the air.

The counterweight trebuchet was so effective that medeival fortification and defense planning began to be redesigned sometime after its introduction around the 1200’s. This includes the use of counterweight trebuchets in defensive positions along castle walls. It was the most substantial advance in weaponry until about the sixteenthh century with the invention of the gunpowder canon that replaced stone hurling machines.